Grandchildren,

Since 2006 I've been blogging at www.northwestladybug.com. Some of the posts on that blog are relevant to this one - so I'm taking the easy way out and simply copying them here.

Here is the first, originally published on June 7th, 2013, shortly after Dad/Thomas/Opa and his descendants convened at the Marin Headlands hostel, just north of San Francisco. Dad asked us to gather because he wanted to bequeath upon his children and grandchildren some of his most personal, meaningful, and historically significant possessions "mit warmen haenden" (with warm hands - while still alive).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My 84-year-old father is a German “Mischling” (a half-Jew) and product of what the Nazis called a “privileged mixed marriage.”

By the time Dad was the age of my twins, 23, he had experienced more tragedy, more near-death experiences, more hunger, and more trauma than most people will experience in their lifetimes.

Dad’s father Carl was Jewish, but my father was brought up in a Christian household. Carl considered himself a German. Not a German Jew and not a Jew. He was simply a German. And he married another German, my grandmother, Irmgard.

As it turns out, Irmgard, by her sole existence as a Gentile, shielded her family from early persecution by the Nazis because the Nazis really hadn’t decided what to do about the “half-Jewish question,” those Jews who lived among Germans, married Germans, were part of the German communities, but were Jewish “by blood.” (You can learn more about this topic in the excellent movie “Conspiracy.”)

Irmgard began to have excruciating headaches in the early 1940s. She assumed it was the pressure of war. Certainly she must have also felt intense personal pressure, knowing that the survival of her Jewish husband and half-Jewish children depended on her sheer existence. In January of 1944, Irmgard died of what turned out to be a brain tumor. At that point, all hell broke loose for my grandfather and his three children, my father and his brother Rainer and sister Ulli.

Ulli was sent to live with her cousin in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in the mountains of Bavaria, while my father, only 15, and his older brother Rainer were left to fend for themselves. My father was sent to a Nazi labor camp.

In March of 1945, just a short month before the end of the war, my father had been allowed to leave the camp by day to work at a warehouse. As it turns out, the warehouse proprietor had been smuggling cigarettes, chocolate and liqueur and knew he was about to be caught.

On March 5, 1945, my father’s hometown of Chemnitz was bombed. Total chaos reigned during those last days and weeks of the war and my father was allowed by the kindly (or maybe just apathetic) proprietor to head home to take care of matters. (“Just be back on Tuesday,” he said.) After days of traveling by any means possible (which meant mostly walking, as the German infrastructure at that point was in complete shambles), my father came upon his beloved childhood home.

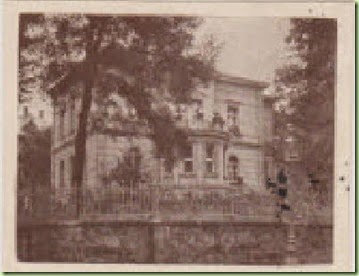

What had once looked like this…

My father, then only 16-years-old, made his way through the rumble and found his beloved father’s body.

Now, in his 84th year, my father passes on two stories and two mementos (though that’s too trivial a word here) from that day to his two grandsons, Peter and Aleks.

Here is the letter that accompanied his gift to Peter:

“Dear Peter,

I have decided to pass on to some of you grandchildren things that mean something to me, and that come with a story that must be told. As “Muttchen,” my pseudo-mother used to say: I want to do so “with warm hands.”

It was in March of 1945, just weeks before the end of the war. I was 16. My mother had already died. I was put into a slave labor camp for “half-Jews,” as they called us.

Now Chemnitz, my home town, had just gotten the same kind of “terror attack,” as the Nazis called it, as Dresden had suffered weeks earlier. My boss, where I had been assigned from the labor camp, was most understanding, if most secretive, about it.

“Go,” he said. “Check out what happened. Just be back by Tuesday at the latest.” Of course there was no telephone, no other news, no transportation. Only chaos everywhere. One just had to make do, somehow.

Our house had been burned out, turned from a burned ruin into mostly rubble. I found my father’s body in the boiler room, caught in the space between the floor and the furnace, one leg dangling, clearly broken.

My father’s body was the only one in the big ruin. I was told later that when the house was on fire everyone got out, including him. Then he had to crawl back into the basement to retrieve a small suitcase with Romanticist art that he was working on. His whole life now had been his art collection; he just HAD to get those pieces. In that moment an explosive bomb hit the house, ending his life, making the three of us orphans.

After escaping the Nazis for a dozen years, now, two short months before the final defeat of Nazi Germany, he was killed by an Allied bomb. Just what the Nazis had always wanted. But any war does that: produce tragic ironies like this, a thousand times over, everywhere.

My dad was wearing a suit, vest, and tie. He was a very formal person and would not be seen in anything but “proper dress,” not even at night in the air raid shelter in his own basement. When I found him, he still had his metal-rimmed glasses on, one side broken. His fingers were apart, indicating that he had not suffered.

I knew there must be one thing he was forced by law to always have on him – his ID card, with the big letter “J” to identify him immediately as a Jew, with the forced name of “Israel” added. I took it and I still have that infamous ID.

He was wearing his diamond tie pin so that his tie would be orderly and in place where it belonged. I took it. Years later, in Munich, in peace, I designed a ring for myself and had the diamond of my father’s tie pin mounted in it.

That ring is what I give to you today. Today, when wearing it, I know that what had meaning to me was not my father’s dying as much as his death. I knew then that his most romantic, often-quoted motto would somehow follow me: Goethe’s most utopian idea that “life, however it may be, is good.” He, a Jew under the Nazis, persecuted, with two sons in Nazi slave labor camps, through all the chaos, kept this idealized faith. And for years it gave me the strength I needed to shape the path of my own life, without parental guidance.

With love, Opa”

And here is what Opa bequeathed upon Aleks, given to him this past weekend during our family reunion:

This is what Opa wrote to Aleks:

Dear Alex –

I have decided to pass on to you grandchildren things that mean something to me, and that come with a story that must be told. As “Muttchen”, my vice mother, used to say: I want to do so “with warm hands.”

Of all my grandchildren, you have been the one with the greatest interest in history and historical events. Therefore, the papers I treasure most of my historical documents will be yours to keep and pass on, eventually. There is, first of all, my father’s “Kennkarte,” the identification everybody in Germany had to carry at all times. (I still do today, and not only my drivers license. out of habit.) In 1934, the Nazis issued the Nürnberger Gesetze which were really not laws at all, but party dictates. Among other edicts, they ruled that Jews from then on had to be identified by the middle (actually first) name “Israel” for men, “Sarah” for women. Jews were defined by race, not religion. By “law”, my father had to always identify himself, especially in official transactions, as “Israel Carl Heumann”, not as “Carl Heumann” or, as had been most common, as “Konsul Heumann.” That way, the official would know exactly what kind of degenerate he was dealing with. Not identifying oneself as such was a felony. In official papers, he was called “der Jude Heumann”. I took this ID from his body which I found in the basement of the ruin of our house in 1945. Don’t forget: the Nazis were most German, most bureaucratic. In 1938, Hermann Goering, in the second line of the Nazi hierarchy, decided on a classification of “privileged mixed marriages” between Jews and Gentiles whose offspring were not raised in the Hebrew religion. Those Jews were subject to the same mistreatments as other Jews, except they were not deportated into camps, until the end of the War. That’s why both my father and we kids were living ostensibly as Christians.

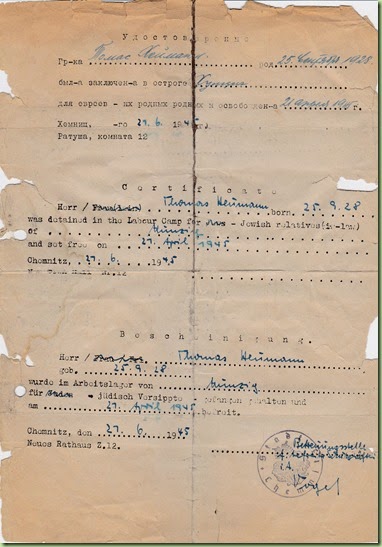

The “Party” was going to deal with the problems of “Half-Jews” after they “had won the war”. Meanwhile, they needed Half-Jews as workers. The document package you are getting also has a three-language paper, issued in June 1945, my most important ID right after the war, saying I was kept in the Slave Labor Camp until April 1945. Also included are documents showing my dismissal from High School in 1943, and an affidavit that I had been a very good guy all along before being kicked out, and also documentation of my freedom from tuition fees at the Technical University in Munich.

Fortunately life has returned to be more normal. Here are a couple of things that we were able to rescue after the war: a silver bowl belonging to my parents, and a set of ice cream server and spoons we used as children at home.

May times like my parents lived through never happen again!

With love, Opa

This is what now belongs to Aleks and will certainly be passed on to his children someday, who will pass it to their own children…

My grandfather’s Nazi ID card. Note that he is identified as “Israel Carl Heumann.” The name "Israel” was mandated by the Nazis.

Affidavit of “total destruction by bombing” of my father’s home:

Certificate of free tuition and monthly stipend because of Nazi persecution.

Certificate regarding my father’s detention in a Nazi labor camp. (In three languages… it reads “Herr Thomas Heumann, born on… was detained in the labor camp for Jewish relatives in-law of Munzig and set free on 27 April 1945. Chemnitz, 27.6.1945. Neues Rathaus.”)

Certificate of release from public school in March, 1943, as well as other education-oriented documents:

My father has been hesitant about allowing me to post about his past, not wanting to “draw attention” to himself and his past. But he has relented a bit recently. Partially, I think, because he is now looking more at the historical importance of his experience, and partially because… well, I’ve been a pest about it, trying to convince him that the Internet will not “turn on him.”

And, sadly, I think that he is also resigning himself to the inevitability of his own passing and the importance of keeping the story of what happened in World War II alive and personalized to specific human experiences.

No comments:

Post a Comment